What happens when you type a Phoenix URL into your address bar and press “Enter”?

Here’s a classic question that I’ve asked and been asked in many job interviews: “What happens when you type a URL into your browser’s address bar and hit Enter?”

A good answer includes a basic explanation of DNS, networking and the structure of an HTTP request and response. But if it was a Phoenix job I might ask a follow-up: “what if the page is rendered by a Phoenix app?”

In order to answer this well, you need a broad understanding of the Phoenix stack: %Plug.Conn{}, Endpoint, the Router, plugs, pipelines, controllers and views. Then if the page is a LiveView, you also need to know about websockets and the LiveView lifecycle, including quirks such as that mount/3 is called twice. So it’s a good question to test your knowledge - and studying the answer is a great way to deepen your understanding of Phoenix.

In this two-part series, I’ll give the high-level overview. First I’ll explain how Phoenix renders a static HTML page for routes that are served by a controller. Then in part 2, I’ll explain what additionally happens if the route is served by a LiveView. And if you want to go deeper, check out my LiveView course at LearnPhoenixLiveView.com.

I’ll illustrate things using a Phoenix app called Example that I generated with mix phx.new example. For part 1 we’ll look at a controller action, ExampleWeb.UserController.index/2, generated with mix phx.gen.html:

$ mix phx.gen.html Accounts User users name:string

See the footnote for a full description of how to build this app.

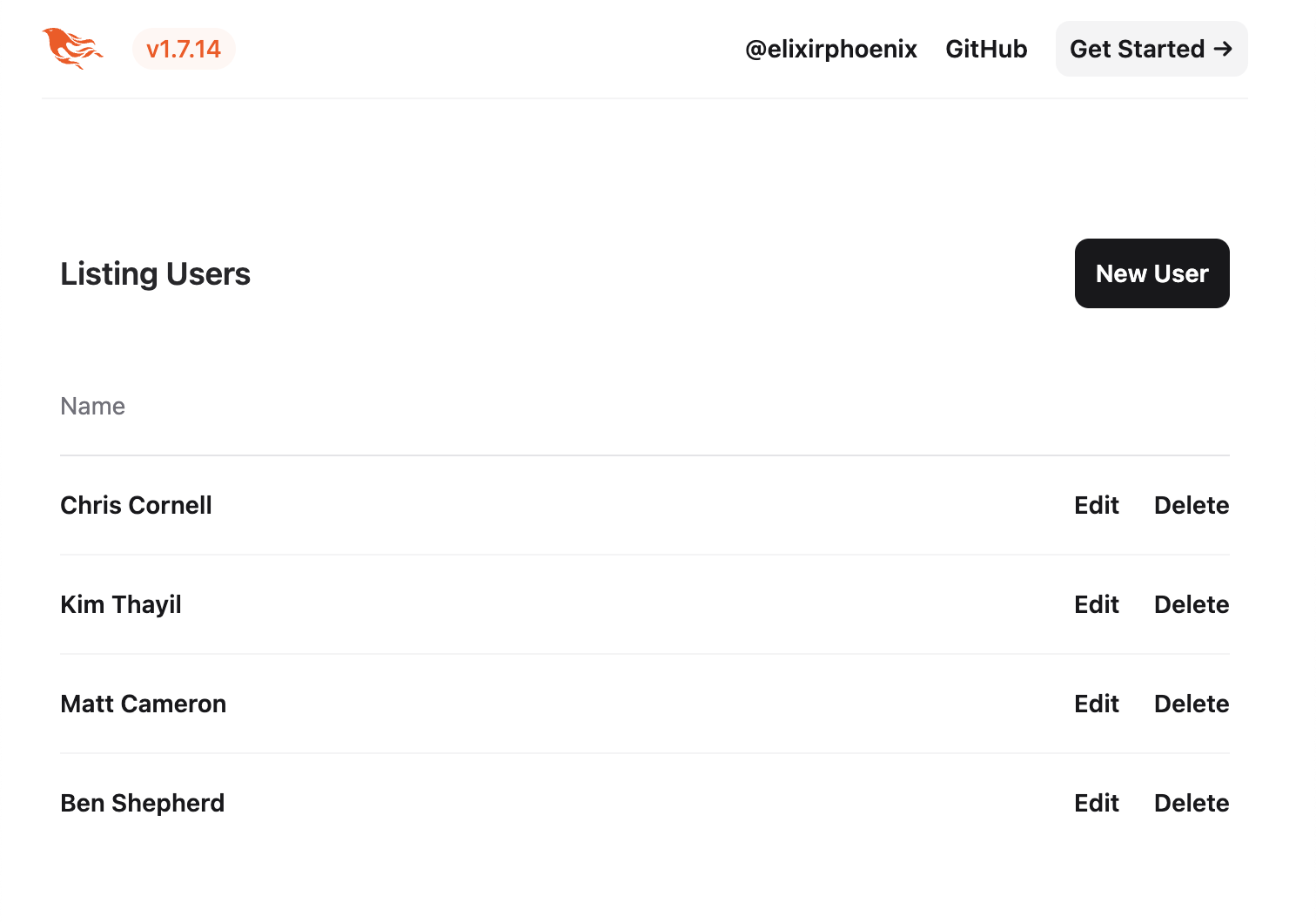

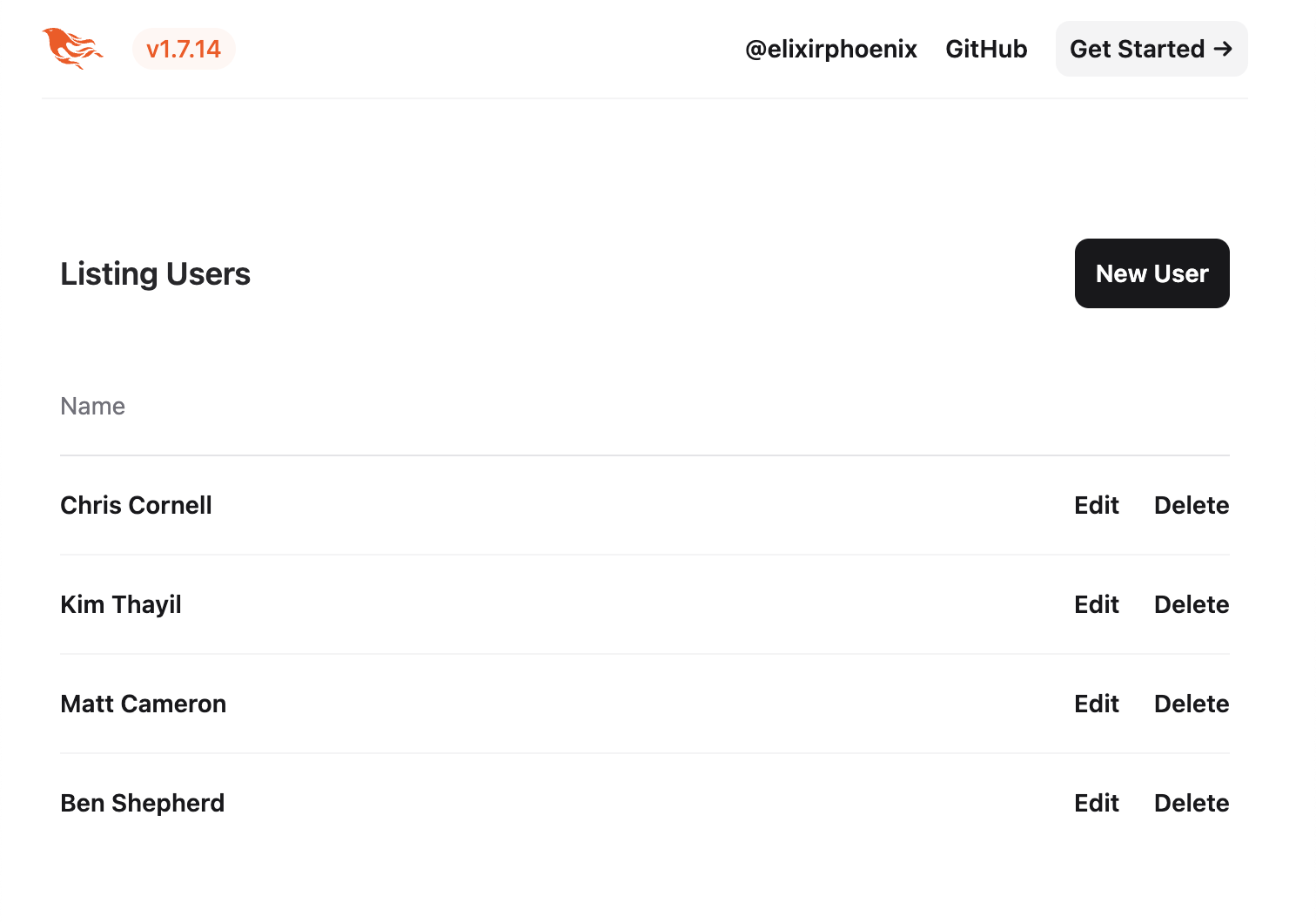

The index action is served on the path /users. So if you start the server locally with mix phx.server then type http://localhost:4000/users into your address bar and hit Enter, you’ll see the user index page:

How did it work?

%Plug.Conn{} and Endpoint

When you hit “Enter”, your browser resolves DNS in the normal way and makes an HTTP GET request like it would for any other URL. The Phoenix server receives this request, and must return an HTTP response.

In Phoenix an HTTP request and its response are represented by an instance of the %Plug.Conn{} struct. When a request comes in, Phoenix initializes a %Plug.Conn{} with the request’s information, and passes it to the app’s Endpoint, which defines a list of plugs:

# lib/example_web/endpoint.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.Endpoint do

use Phoenix.Endpoint, otp_app: :example

…

plug Plug.Static,

at: "/",

from: :example,

gzip: false,

only: ExampleWeb.static_paths()

…

plug Phoenix.LiveDashboard.RequestLogger,

param_key: "request_logger",

cookie_key: "request_logger"

# Code reloading can be explicitly enabled under the

# :code_reloader configuration of your endpoint.

if code_reloading? do

…

plug Phoenix.LiveReloader

plug Phoenix.CodeReloader

plug Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus, otp_app: :example

end

plug Plug.RequestId

plug Plug.Telemetry, event_prefix: [:phoenix, :endpoint]

plug Plug.Parsers,

parsers: [:urlencoded, :multipart, :json],

pass: ["*/*"],

json_decoder: Phoenix.json_library()

plug Plug.MethodOverride

plug Plug.Head

plug Plug.Session, @session_options

plug ExampleWeb.Router

end

A plug is a 2-arity function, or a module with a function call/2, that takes and returns a %Plug.Conn{}. Endpoint specifies a list of plugs to pass the incoming %Plug.Conn{} through. So if conn is the initial %Plug.Conn{} representing the raw request, then Endpoint is effectively doing this:

conn

|> Plug.Static.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveDashboard.RequestLogger.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.CodeReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus.call()

|> Plug.RequestId.call()

|> Plug.Telemetry.call()

|> Plug.Parsers.call()

|> Plug.MethodOverride.call()

|> Plug.Head.call()

|> Plug.Session.call()

|> ExampleWeb.Router.call()

At each step in the chain, we take the %Plug.Conn{} from the previous step, update it, and pass it on to the next function. (Each plug also takes a keyword list of options as its second argument, but I’m omitting that here for simplicity’s sake.)

Endpoint defines the universal behavior to apply to every incoming HTTP request. For example, the function Plug.RequestId.call/2 assigns the request a unique ID that will be used when logging.

Note that three of the plugs in Endpoint - Phoenix.LiveReloader, Phoenix.CodeReloader, and Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus - are wrapped in the conditional if code_reloading?, which is only true in the :dev environment. So those three plugs won’t be called in tests or production.

The last plug in the Endpoint is ExampleWeb.Router - the router.

Routing

The router’s job is to figure out which specific part of the codebase - which LiveView or controller - should handle this particular request. In our example app, the router defines resources routes at the /users path:

# lib/example_web/router.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.Router do

use ExampleWeb, :router

…

scope "/", ExampleWeb do

pipe_through :browser

…

resources "/users", UserController

end

Note the scope block with pipe_through - we’ll discuss this in a minute.

If you run mix phx.routes you can see that resources defines eight routes:

$ mix phx.routes

…

GET /users ExampleWeb.UserController :index

GET /users/:id/edit ExampleWeb.UserController :edit

GET /users/new ExampleWeb.UserController :new

GET /users/:id ExampleWeb.UserController :show

POST /users ExampleWeb.UserController :create

PATCH /users/:id ExampleWeb.UserController :update

PUT /users/:id ExampleWeb.UserController :update

DELETE /users/:id ExampleWeb.UserController :delete

…

Our incoming request is to GET /users, which matches the first of those:

GET /users ExampleWeb.UserController :index

So this request will be handled by the index action of the UserController controller. But the routes were defined within a scope block containing the line pipe_through :browser. So before UserController can do anything, we must pipe the %Plug.Conn{} through the :browser pipeline:

# lib/example_web/router.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.Router do

use ExampleWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_live_flash

plug :put_root_layout, html: {ExampleWeb.Layouts, :root}

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

…

Like Endpoint, this defines another chain of functions to pass the %Plug.Conn{} through. So it basically does this:

conn

|> Phoenix.Controller.accepts()

|> Plug.Conn.fetch_session()

|> Phoenix.LiveView.Router.fetch_live_flash()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_root_layout()

|> Phoenix.Controller.protect_from_forgery()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_secure_browser_headers()

(Again, I’m omitting details about these functions’ second arguments.)

This defines shared behavior for all routes that are intended to be accessed using a web browser. For example, Phoenix.Controller.protect_from_forgery/2 guards against CSRF attacks, while Phoenix.Controller.accepts/2 performs content negotiation.

We don’t put this in Endpoint because not every HTTP request will necessarily be from a browser. An API-only route could skip this pipeline, for example.

Putting it all together, our original %Plug.Conn{} has been transformed by a long chain of functions:

conn

|> Plug.Static.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveDashboard.RequestLogger.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.CodeReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus.call()

|> Plug.RequestId.call()

|> Plug.Telemetry.call()

|> Plug.Parsers.call()

|> Plug.MethodOverride.call()

|> Plug.Head.call()

|> Plug.Session.call()

|> Phoenix.Controller.accepts()

|> Plug.Conn.fetch_session()

|> Phoenix.LiveView.Router.fetch_live_flash()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_root_layout()

|> Phoenix.Controller.protect_from_forgery()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_secure_browser_headers()

At the end we get an updated %Plug.Conn{}. As specified by the router, Phoenix passes it to UserController.index/2:

# lib/example_web/user_controller.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.UserController do

use ExampleWeb, :controller

alias Example.Accounts

alias Example.Accounts.User

def index(conn, _params) do

users = Accounts.list_users()

render(conn, :index, users: users)

end

…

This function’s first argument, conn, is the %Plug.Conn{} that was returned at the end of the pipeline. The controller’s job is to return another, finalised %Plug.Conn{} with all the information Phoenix needs to render the final response to the HTTP request.

In this case we load all users from the database using Accounts.list_users/0, then we use render/2 to render them in an HTML response using the :index template. This uses the UserHTML view:

# lib/example_web/controllers/user_html.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.UserHTML do

use ExampleWeb, :html

embed_templates "user_html/*"

…

end

The embed_templates macro tells Phoenix to look for the index template at lib/example_web/controllers/user_html/index.html.heex:

<.header>

Listing Users

<:actions>

<.link href={~p"/users/new"}>

<.button>New User</.button>

</.link>

</:actions>

</.header>

<.table id="users" rows={@users} row_click={&JS.navigate(~p"/users/#{&1}")}>

<:col :let={user} label="Name"><%= user.name %></:col>

<:action :let={user}>

<div class="sr-only">

<.link navigate={~p"/users/#{user}"}>Show</.link>

</div>

<.link navigate={~p"/users/#{user}/edit"}>Edit</.link>

</:action>

<:action :let={user}>

<.link href={~p"/users/#{user}"} method="delete" data-confirm="Are you sure?">

Delete

</.link>

</:action>

</.table>

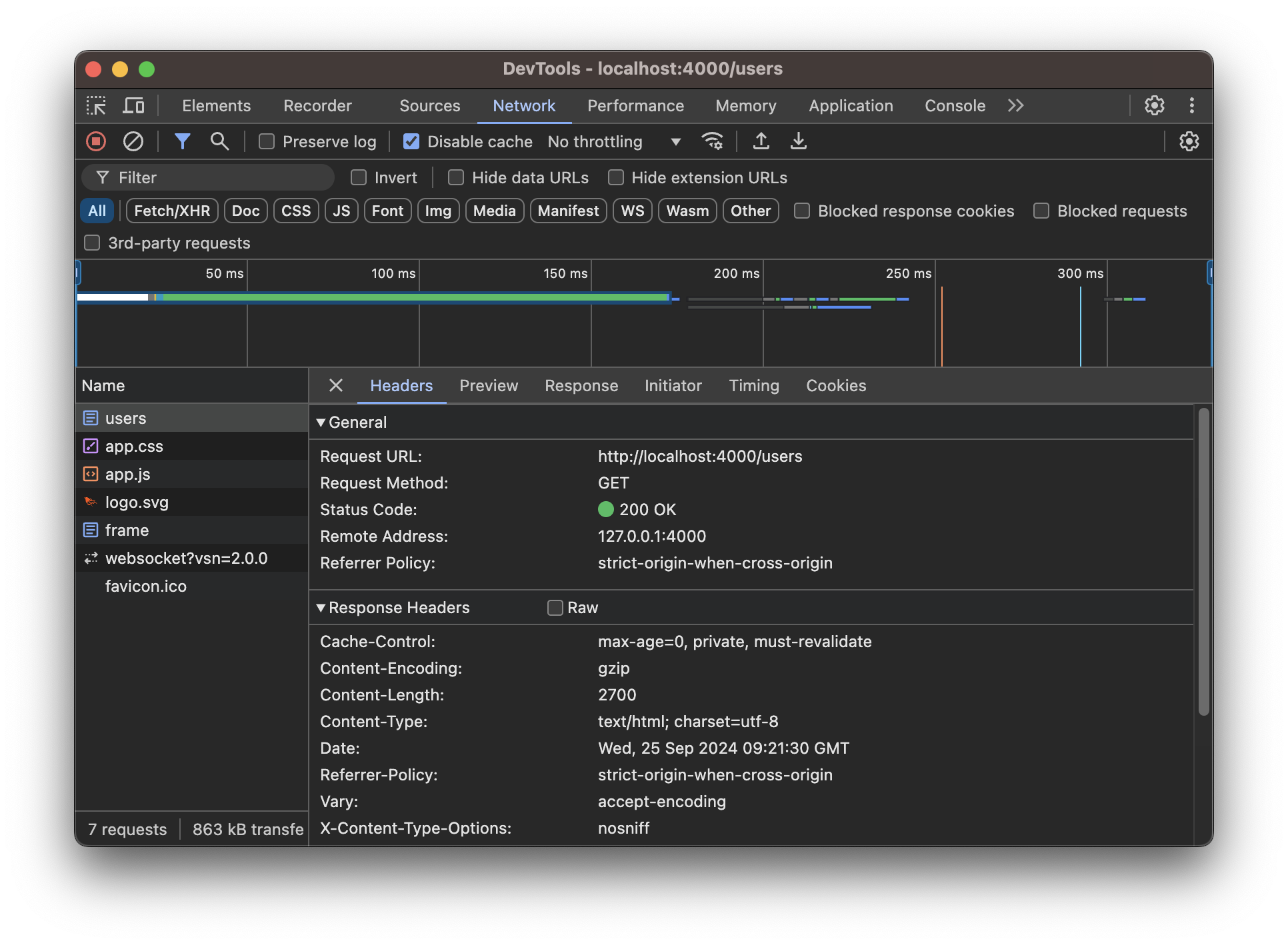

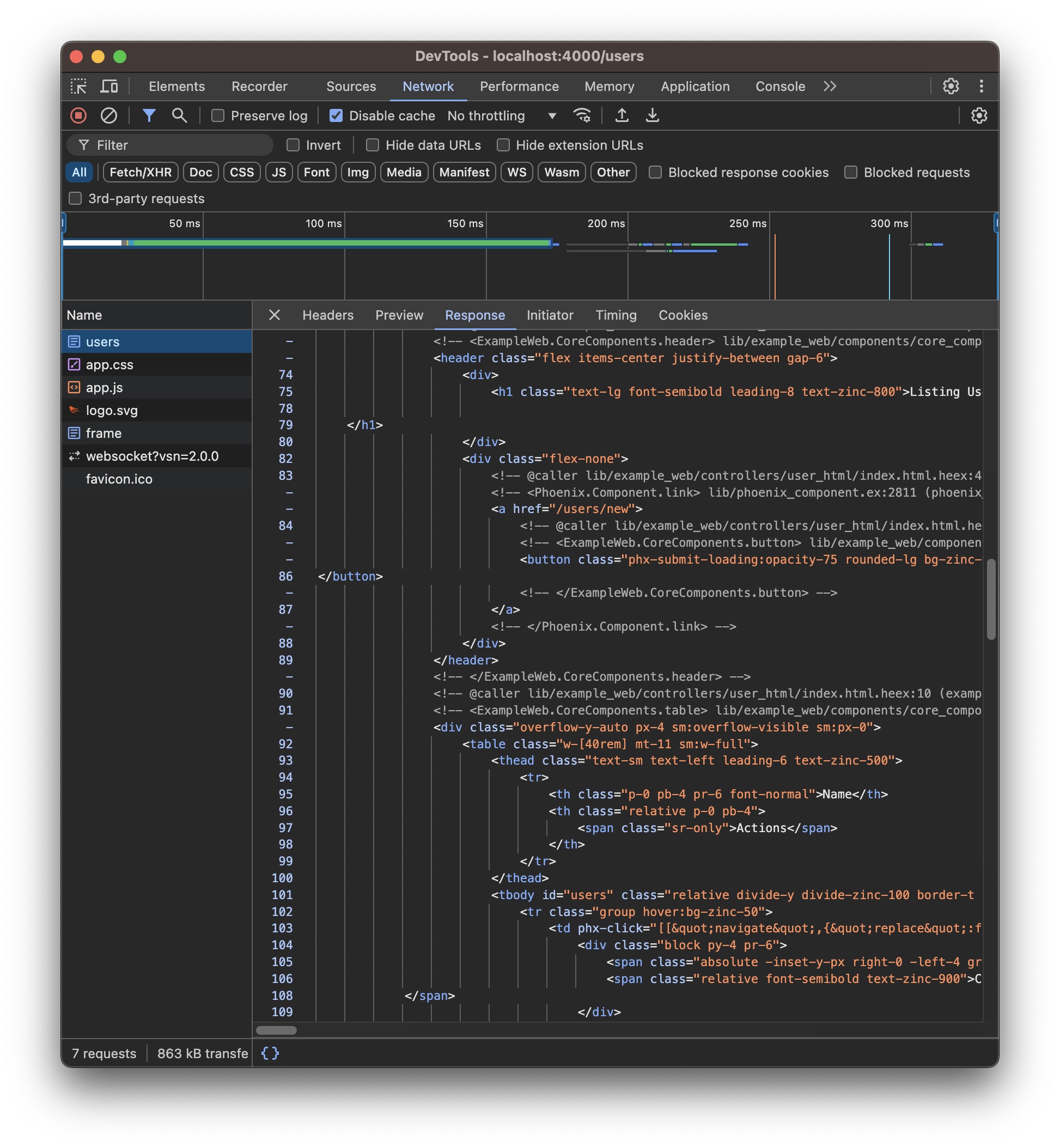

This HEEx (“HTML + Embedded Elixir”) is used to generate an HTML response that render/2 stores within the %Plug.Conn{}. Phoenix uses this final %Plug.Conn{} to return a response to the HTTP request, as we can see in the browser’s network inspector:

The response body includes the HTML:

And that HTML, of course, gets rendered like this!

Controller actions don’t have to render an HTML template. For example, we could use redirect/2 to return a 302 response that redirects the user to an interesting video:

def index(conn, _params) do

redirect(conn, external: "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQw4w9WgXcQ")

end

Or we could use send_resp/3 to manually set the HTTP response code and body.

def index(conn, _params) do

send_resp(conn, 404, "Not found")

end

All that matters is that the controller returns a %Plug.Conn{} containing enough information for Phoenix to return a valid HTTP response.

Additionally, if the controller doesn’t return a %Plug.Conn{}, you can use action_fallback/1 to define fallback behavior. But that’s a slightly more advanced topic. For an example of action_fallback/1 in action, try running mix phx.gen.json and checking out the generated controllers.

Phoenix is also smart enough to handle exceptions gracefully. For example, if Ecto raises an Ecto.NoResultsError because you’re trying to load data that doesn’t exist, Phoenix will catch this and return a 404. Or if an error is raised that doesn’t have a specific handler - e.g. a RuntimeError caused by some broken code - Phoenix will return a generic 500 error page.

It’s function calls all the way down

As we saw, the Endpoint calls this chain of functions:

conn

|> Plug.Static.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveDashboard.RequestLogger.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.CodeReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus.call()

|> Plug.RequestId.call()

|> Plug.Telemetry.call()

|> Plug.Parsers.call()

|> Plug.MethodOverride.call()

|> Plug.Head.call()

|> Plug.Session.call()

|> ExampleWeb.Router.call()

And when the request is to GET /users, the last function in that chain (ExampleWeb.Router.call/2) equates to this, running six plugs from the :browser pipeline plus a controller action:

conn

|> Phoenix.Controller.accepts()

|> Plug.Conn.fetch_session()

|> Phoenix.LiveView.Router.fetch_live_flash()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_root_layout()

|> Phoenix.Controller.protect_from_forgery()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_secure_browser_headers()

|> ExampleWeb.UserController.index()

Putting it all together, the entire request-response cycle is just a long chain of functions that update a %Plug.Conn{}. In goes a request, out comes a response:

conn

|> Plug.Static.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveDashboard.RequestLogger.call()

|> Phoenix.LiveReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.CodeReloader.call()

|> Phoenix.Ecto.CheckRepoStatus.call()

|> Plug.RequestId.call()

|> Plug.Telemetry.call()

|> Plug.Parsers.call()

|> Plug.MethodOverride.call()

|> Plug.Head.call()

|> Plug.Session.call()

|> Phoenix.Controller.accepts()

|> Plug.Conn.fetch_session()

|> Phoenix.LiveView.Router.fetch_live_flash()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_root_layout()

|> Phoenix.Controller.protect_from_forgery()

|> Phoenix.Controller.put_secure_browser_headers()

|> ExampleWeb.UserController.index()

That’s the beautiful elegance of Phoenix. A lot is happening, but at the end of the day it’s nothing more than a list of functions that each take and return the same kind of struct. You can understand each step in the chain without an advanced knowledge of Phoenix’s inner workings, because Phoenix is not your application.

So when you type a Phoenix URL into your address bar and press “Enter”, that’s how Phoenix returns an HTTP response. For a controller, we’re done, but if the page is a LiveView, this is only the beginning - we also need to open a websocket. That’s the topic of my next post.

Footnote - generating the sample app

Here’s how I created the Example app:

$ mix phx.new.example

Fetch and install dependencies? [Yn] Y

$ cd example

$ mix ecto.create

$ mix phx.gen.html Accounts User users name:string

Add the resources to the router as per the instructions printed by the phx.gen.html generator:

# lib/example_web/router.ex

defmodule ExampleWeb.Router do

use ExampleWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_live_flash

plug :put_root_layout, html: {ExampleWeb.Layouts, :root}

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

pipeline :api do

plug :accepts, ["json"]

end

scope "/", ExampleWeb do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :home

+

+ resources "/users", UserController

end

…

Run the migration that the generator added:

$ mix ecto.migrate

Then start the server on localhost:4000:

$ mix phx.server

[info] Running ExampleWeb.Endpoint with Bandit 1.5.7 at 127.0.0.1:4000 (http)

[info] Access ExampleWeb.Endpoint at http://localhost:4000